FAQs

There are a number of ongoing studies, many of which are using randomized controlled trial designs. The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) is currently funding studies in Las Vegas and Los Angeles. The Laura and John Arnold Foundation is funding studies in Spokane (Washington), Tempe (Arizona), Anaheim (California), Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania), and Arlington (Texas), as well as a national cost-effectiveness study. A number of other research studies are underway or in the planning stages in the United States and United Kingdom, including Pensacola (Florida), West Palm Beach (Florida), Orlando (Florida), Greenwood (Indiana), Miami Beach (Florida), Oakland (California), and the Isle of Wight and Essex (United Kingdom).

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) has dedicated $2 million to fund two or three body-worn camera (BWC) projects as part of the Smart Policing Initiative in fiscal year 2015. As part of President Obama's Community Policing Initiative, $20 million is available to support BWC purchases and programs in fiscal year 2015. The President has proposed an additional $30 million in the fiscal year 2016 budget. Finally, the BJA Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) is a valuable resource for communities to use to procure this equipment.

For more information, see:

There is potential to integrate body-worn cameras (BWCs) with facial recognition systems and other new technologies like live feed and auto recording. The use of facial recognition and BWCs may pose serious risks to public privacy. Agencies that explore this integration and other new technologies should proceed very cautiously and should consult with legal counsel and other relevant stakeholders.

Collaborating on a body-worn camera (BWC) policy among all interested parties from a county ensures that all parties follow the same policies and evidence retention schedule. Regional collaboration would establish consistent processes from law enforcement to the district attorney. Santa Clara County, California collaborated on a model policy that involved the county law enforcement agencies, the district attorney, and California Highway Patrol. This BWC model policy serves as an effective example of county-wide collaboration. However, such collaborative efforts might be more difficult in other jurisdictions and result in long delays in BWC implementation. Communities need to weigh the costs and benefits of collaboration and determine the best course of action for their jurisdiction over the short, medium, and long term.

Yes, there is some evidence that suggests that body-worn cameras (BWCs) improve the likelihood of successful prosecutions. In Phoenix, Arizona, a Bureau of Justice Assistance-sponsored project examined the impact of BWCs on domestic violence case processing, concluding the following: “Analysis of the data indicated that following the implementation of body cameras, cases were significantly more likely to be initiated, result in charges filed, and result in a guilty plea or guilty verdict. The analysis also determined that cases were completed faster following the implementation of body cameras, [in part because of the] addition of a court liaison officer who facilitated case processing between the Phoenix Police Department and city prosecutor’s office” (Katz et al., 2015).

While there has been little research about this issue, it is clear that an agency needs to carefully consider its policy options with respect to the release of video that may contain sensitive footage. As agencies develop policies, they need to be mindful of the impact of the video release on victims, suspects, police officers, businesses, witnesses, family members, and the investigation and prosecution of the case. In the absence of clear policy, the release of sensitive video might be left to the discretion of an administrator or a redaction specialist on a case-by-case basis.

A small or tribal agency could use the same documents on technology and implementation as any other agency. One key difference might be in policy development. The deployment of body-worn cameras (BWC) might have different policy implications for town, township, village, or tribal law enforcement agencies. Agencies should identify key reasons for developing a BWC program and what laws, rules, and cultural expectations are specific to them. Small and tribal agencies also need to be especially mindful of how their BWC program will be affected by personnel and resource limitations in their agency. They can search the BWC Toolkit to find policy references relevant to their agency size or type.

A two-page Body-Worn Camera (BWC) Law Enforcement Implementation Checklist was created for your download and use in implementing a new body-worn camera program from learning the fundamental all the way to a phased rollout. This guide captures the seven key focus areas to a comprehensive program plan and provided references back to this BWC Toolkit where relevant.

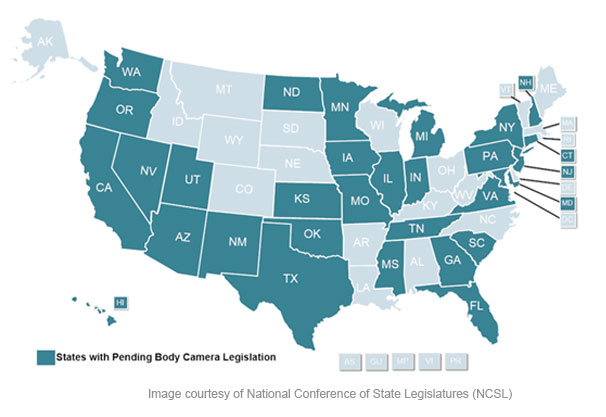

Per the National Conference of State Legislatures, an increasing number of states—30 as of Feb. 20—are considering legislation that address body-worn cameras for police officers.

Proponents of body-worn cameras believe that video and audio recordings of law enforcement’s interactions with the public will provide the best evidence of, and defense to, accusations of police misconduct. They also believe that being on camera reduces some tension between police officers and the public. For example, a field experiment conducted on body-worn cameras with the Rialto, CA, Police Department found that incidents where police used force and community member complaints against police officers were reduced 50 and 90 percent respectively compared to the previous year.

Several municipalities—including Chicago (IL), the District of Columbia, Los Angeles (CA), New York (NY) and Seattle (WA)—have recently implemented body-worn camera programs and their experiences will inform body-worn camera policy moving forward.

While many are enthusiastic about the potential benefits of body-worn cameras, there are practical and constitutional hurdles to their implementation including funding, data storage and retention, open records laws, recording in areas protected by the Fourth Amendment and appropriate regulations for police use. Many of these and other issues are addressed in state legislation.

So far there have been few enactments addressing body-worn cameras by police officers, and all became law in 2014. Pennsylvania (30 Pa.C.S.A. § 901, PA ST 34 Pa.C.S.A. § 901) enacted legislation allowing waterway and game conservation officers to wear body-worn cameras and Vermont (VT ST T. 20 § 2367) enacted a law that, in part, requested a study of their use in conjunction with Tasers. Oklahoma enacted a law classifying video and audio files from body-worn cameras, if kept, as records under their Open Records Law. Oklahoma’s (51 Okl.St.Ann. § 24A.8) law also specified situations where video could be redacted prior to being released including portions that depict the death of a person or a dead body, nudity or the identity of individuals younger than 16 years of age.

Evaluations of BWC programs vary is scope and nature. At a minimum, however, we believe that the implementing agency should consider conducting both process and impact evaluations. The process evaluation should capture the planning and deployment process, including the names of officers who have been assigned cameras. These officers should undergo routine compliance audits to determine whether they are activating their BWC when required by departmental policy. These audit reports should be provided to the officer and their supervisor on a monthly basis, and should be compiled into an annual department wide compliance report. This annual report should be provided to the community’s risk management unit. Impact evaluations vary considerably in their methodological rigor, from one group pre-post studies to randomized controlled trials. Generally, the more rigorous the better. The impact evaluation should, at a minimum, compare various outcome measures by individual assigned a BWC one year pre and postimplementation. Outcome measures examining the impact of the BWC’s might include number of complaints, number of complaints sustained, use of force incidents, and number of resisting arrest incidents. For example, a department might compare the number of complaints one year prior to an officer being assigned the BWC to the one year period following the assignment of the BWC. For many agencies it is helpful to partner with a local college or university to evaluate the implementation of the BWC program, particularly in the programs first few years of implementation.

For more information, see:

Questions from community members are likely to focus on several key issues. The first involves aspects of BWC policy. For example, citizens will likely ask questions such as: when will officers turn the camera on? Do they have to tell me before they turn it on? Can I ask the officer to turn the camera off? Am I allowed to request a copy of the video?

Citizens are also likely to ask privacy-related questions, such as: Are officers allowed to film in my house or apartment? What happens if the officer records my children? Who is allowed to watch the video? Is this video going to end up on the internet or YouTube? Will my neighbor be able to see this video? Citizens may also want to know about the goals of the BWC program. They may ask: Why are police officers wearing BWCs? What does the agency hope to accomplish with BWCs? Will all officers be wearing cameras? BWCs will have a significant impact on citizens, and community buy-in is critical to the success of a BWC program. As a result, Law enforcement agencies should be prepared to provide detailed responses to these and other questions.

Each department must fully examine its state, local, and tribal laws to determine when it is lawful to record events. Most communities, however, fall into one of two groups.

The first group is composed of those communities that require one-party consent. In these communities it is lawful to record communication when consent is obtained from one person (e.g., officer, suspect, or victim). Within these laws, there might already be exceptions that would cover body-worn cameras (BWC). Nonetheless, in these communities, it is up to law enforcement to determine whether they inform the individual of the recording. The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) recommends that officers inform members of the public that they are being recorded "unless doing so would be unsafe, impractical, or impossible," (PERF, 2014: 40). PERF emphasizes that this does not mean that they are required to have consent to record, only that they inform the person that they are recording. The rationale for this is straightforward. If BWCs do produce benefits in terms of change in behavior (civilizing effect), those benefits can only be realized if the community member is aware of the recording.

The second group are those communities that require two-party consent. This means that it is not legal to record the interaction unless both parties consent to it being recorded. As stated above, there might also be exceptions within these laws that may cover BWC recordings. Two-party consent laws can present special problems to law enforcement agencies that are interested in implementing a BWC program because the law enforcement officers have to announce that they would like to record the interaction and obtain approval from the member of the public. As a consequence, some states such as Pennsylvania have successfully modified existing statutes to allow the law enforcement to use BWCs without two-part consent (Mateescu, Rosenblat and Boyd, 2015).

For more information, see:

- Data and Society Police Body-Worn Cameras (Mateescu, Rosenblat and Boyd, 2015): http://www.datasociety.net/pubs/dcr/PoliceBodyWornCameras.pdf

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

The decision by a law enforcement agency to implement a body-worn camera (BWC) program represents an enormous investment of time and resources. The following are some of the concerns related to BWC programs:

- Buying the hardware and managing the data: In January 2015, the acting Chief of the Phoenix (AZ) Police Department announced that it would cost the department $3.5 million to outfit its 3,000 officers with body-worn cameras and manage the BWC program. Overall, the costs vary depending on the type of camera, type of storage, IT support, and use of video. Agencies have been able to save money by joining with other agencies to purchase cameras and storage.

- Privacy considerations: Privacy rights of the public are a primary concern. BWCs have the potential to impinge on community members' expectation of privacy. The technology may also present concerns for vulnerable populations such as children and victims of crime. Law enforcement agencies should fully investigate state privacy laws and engage relevant stakeholder groups (e.g., victim advocacy groups) before adopting BWCs. Officer privacy should also be addressed. Some law enforcement unions have opposed BWCs, arguing that adoption of the technology must be negotiated as part of the collective bargaining agreement. Also, at the February 26-27, 2015 Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel, some of the audience expressed concerns about BWCs because the technology gives supervisors the opportunity to go on "fishing expeditions" against officers in their command. Discussions among law enforcement executives and line officers are an important aspect of the policy development for implementing a BWC program.

- Prosecution: Prosecutors and defense attorneys will want to review BWC video related to their cases, but they too have an obligation to protect the privacy of community members captured in the video. Therefore, it is important that the impact on prosecutorial and defense bar resources is taken into account when implementing a BWC program.

- Policy development: During the BWC Expert Panel, participants shared very specific concerns and examples about BWC policy. For instance, Maggie Goodrich of the Los Angeles Police Department discussed her agency's concerns about ensuring officers always consider safety first and not put themselves in danger because of any additional distraction caused by the cameras. Assistant Chief Michael Kurtenbach of the Phoenix (AZ) Police Department walked through an example of a video used in a prosecution that resulted in an assault conviction of the officer. Triggered by the egregious behavior in the video, the agency reviewed three months of prior video to discover a pattern of inappropriate behavior. Upon the officer’s termination, the police union expressed concerns about evaluation of prior video, because the department had said it would not use video for administrative purposes. Kurtenbach suggested this illustrates the need for thoughtful consideration of policies even though, in this example, "once the videos were seen everyone agreed the officer should be fired."

- Training considerations: Law enforcement agencies should plan for additional training on camera use, video review, and video expungement and redaction.

- Advocacy considerations: Cynthia Pappas from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention reminded BWC Expert Panel participants that "95% of youth and juveniles commit non-violent offenses so there should be great precautions made to protect them, including protections from public screening" of the video. Krista Blakeney-Mitchell from the Office on Violence Against Women went on to describe how victim confidentiality should be addressed during a call for assistance for domestic violence. If an officer is entering the home of a domestic violence victim, the victim is exposed. "We need to consider how that plays out later in recordings. Will the video be used against the victim based on her demeanor near the time of the incident? Will she be re-victimized?" Another concern is the use of BWCs when dealing with sexual assault victims and the need to decide how video will be used in these situations. Lastly, Blakeney-Mitchell explained that it is "hard for victims to come forward when everyone will know their story based on video footage…there is a concern that victim reporting will go down."

For more information, see:

There are significant concerns regarding the recording of interviews with crime victims and other vulnerable populations (e.g., children and the mentally ill). Victims of crime have experienced a traumatic event and law enforcement officers should be sensitive to the possibility that recording their interaction with the victim may exacerbate that trauma. The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) report (PERF, 2014) recommends that officers always obtain consent to record interviews with crime victims and that consent should be recorded by the body-worn camera (BWC) or obtained in writing. Officers should also be aware of the laws governing the recording of interviews with juveniles, which may vary from laws governing adults. Officers may require additional training regarding the recording of interviews with vulnerable populations.

Participants in the February 26-27, 2015 Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel discussed the understandable fears victims express about the public release of their recorded statements. Damon Mosler, Deputy District Attorney of San Diego (CA) County, suggested those concerns are broader than one may initially consider. "Most policies record all law enforcement activities, but you will capture confidential, biographical, and financial data of victims and witnesses. What are victim impacts for juveniles being recorded? What about informants caught on tape? Ancillary bystanders–when you have multiple officers responding, you have different tapes. Some may shut off, some may not." Panel participants also discussed the fear victims may have about how the video could be used against them.

Further illustrating the complexity of this issue, Maggie Goodrich from the Los Angeles (CA) Police Department shared that during discussions with victims' rights advocates, the LAPD found that "some want recordings–such as when a victim is being interviewed by an expert in a rape treatment center, yet some are concerned that victims' memories right after trauma is initially fuzzy and may become clearer over time, and prosecutors don't necessarily want two different statements."

For more information, see:

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

Law enforcement agencies will benefit from a public education campaign that is focused on increasing public awareness of the body-worn camera (BWC) program, the goals for the program (why the agency has adopted the cameras), and what to expect in terms of benefits and challenges. The public education campaign can be part of a larger effort by the agency to demonstrate transparency and to improve outcomes with the community. The local media can be an important partner in the public education campaign, through print, radio, and television reporting on the BWC program. Decisions about how much information to provide and how to provide it (web site, public service announcements, media reporting, etc.) should be made locally.

Several participants of the Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel shared their community outreach efforts. Michael Wagers, Chief Operating Officer of the Seattle (WA) Police Department, explained Seattle took three months to rewrite its BWC policy because it posted the policy publically to seek input from stakeholders. Wagers emphasized the significant value in this approach, "We had an agreement with the police union and included them in the policy development process–we ended up using a lot of input from external stakeholders as well." Inspector Steve Goodier of the Hampshire Constabulary in the United Kingdom suggested a pre- and post-survey of both the community and officers, explaining that it was wonderful to have the data to demonstrate internal and external support of BWCs ("85% support among the public support as well as overwhelming positive support from officers").