FAQs

Law enforcement agencies should consult with their local prosecutors and legal counsel as they design their data storage policies. Laws governing how long video must be stored may vary across cities, tribal governments, and states. Video that depicts an arrest or critical incident may have to be stored for an extended period of time. Departments have varied policies on how long they keep video that depicts an encounter where no formal action is taken. Some departments will store such video as long as a community member can file a complaint. For example, if members of the public can file a complaint for up to six months after an encounter with a law enforcement officer, it may be necessary to keep all video for six months so the video can be accessed to assist with the complaint investigation. State law may dictate the length of time for storage of more formal law enforcement encounters with members of the public. These are important issues that law enforcement agencies should discuss with their prosecuting authority before procuring storage systems or enacting any policies regarding storage.

Some departments classify body-worn camera video as either "evidentiary" or "non-evidentiary." Evidentiary video includes footage that can be used for investigative purposes, and many departments have created sub-classification systems of types of videos (homicide, use-of-force, arrest, mental health commitment, etc.). The length of time a video is retained is then typically determined by how the video is classified (evidentiary or non-evidentiary) and, if evidentiary, the type of encounter.

Many of those surveyed by the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) retain non-evidentiary video for 60-90 days. Regardless, retention times should be specifically stated in department policy, as should the process for data deletion. As an indicator of transparency, many departments publicly post their retention policies on their web site.

The PERF report (PERF, 2014) also identifies a number of data storage issues that should be covered by policy and put in place:

- The policy should clearly prohibit data tampering, editing, or copying.

- There should be technological protections against tampering.

- The department should have an auditing system in place that documents who accesses each video, when the access occurs, and why.

- The policy should identify who has authority to access video.

- Departments should develop a reliable back-up system for video.

- Law enforcement should provide guidance on when officers should download video (e.g., at the end of the shift).

- The policy should be explicit about the use of third-party vendors.

Results from the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) surveys of law enforcement executives demonstrate that a number of agencies have engaged with their residents in a positive way regarding the deployment of body-worn cameras (BWC). A number of departments have used adoption of BWCs as an opportunity to demonstrate transparency to the community. Numerous experts strongly recommend engaging in dialogue with members of the public about BWCs before the technology is deployed on the street. Chief Farrar of the Rialto (CA) Police Department stated, "You have to engage the public before the cameras hit the street. You have to tell people what the cameras are going to be used for, how everyone can benefit from them." (PERF, 2014: 21) Other agencies, such as the Los Angeles (CA) Police Department, have solicited community input regarding the development of their administrative policy, and many agencies have used social media to engage residents on the technology.

The February 25-26, 2015 Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel participants emphasized that BWC programs are only one piece of the puzzle, offering the following thoughts:

- "Just because I put on a camera doesn't mean that it's building a relationship or more trust. Police departments needs to use the cameras as part of a larger engagement strategy." Joe Perez, President, Hispanic American Police Command Officers Association – National Capitol Region

- "Trust needs to be established. How can we establish more trust amongst those we serve? There should be more dialogue on this topic rather than on logistics." Dr. Michael D. White, Arizona State University

- "We are posting our video to a YouTube page with redacted videos as a pilot to get transparency and accountability up and requests for videos down." Michael Wagers, Chief Operating Officer, Seattle (WA) Police Department

- "Over the last two years there has been a change; more transparency and legitimacy in policing, and the government invested more money (increased to £6 million pounds) into the BWC program." Inspector Steve Goodier, Hampshire Constabulary, United Kingdom

There is potential to integrate body-worn cameras (BWC) with facial recognition systems. The use of facial recognition and BWCs may pose serious risks to public privacy. Agencies that explore this integration should proceed very cautiously and should consult with legal counsel and other relevant stakeholders.

Departments vary in how they have implemented body-worn camera (BWC) programs. However, there are two common themes.

First, the vast majority of departments have implemented their BWC programs with officers assigned to patrol. The rationale for deploying the technology with front-line patrol officers is that officers on patrol have the most contact with the public. Some departments have also expanded their use of BWCs beyond patrol into specialized units such as K-9, SWAT, specialized driving under the influence teams, and investigations.

Second, many departments have adopted an incremental approach to deployment by restricting use to a small number of officers for an initial pilot period. Departments have found that this type of approach helps to overcome potential officer anxiety and resistance and enables a department to make mid-term revisions as it learns how this technology affects the community as a whole. Such a strategy also allows other units in the department the time to adapt to the new technology. In many cases, the initial group of officers assigned to wear cameras are volunteers who often become "internal champions" for the technology.

Lindsay Miller from the Police Executive Research Forum stated, "The decision to implement a BWC program should not be entered lightly–once implemented it is hard to scale back from that course. Agencies need to thoughtfully examine the idea of a BWC program and have written policies in place (something not all agencies do)."

Currently, we do not have an accurate estimate of the number of law enforcement agencies that have initiated body-worn camera (BWC) programs. Several law enforcement agencies in the United Kingdom were experimenting with BWCs as far back as 2005. In August 2013, the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) surveyed 500 law enforcement agencies regarding their use of BWCs. Of the 254 agencies that responded, just 25% (n=63) indicated that they deployed BWCs. Interest in the technology has grown tremendously since then. One BWC vendor advertised in February 2015 that its product has been purchased by 4,000 law enforcement agencies worldwide, but this figure has not been verified. One expert has estimated that between 4,000 and 6,000 law enforcement agencies are planning to adopt or have already adopted BWCs. The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) is performing a survey to better understand the number of law enforcement agencies that have implemented a BWC program.

For additional information, see:

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS): http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5279

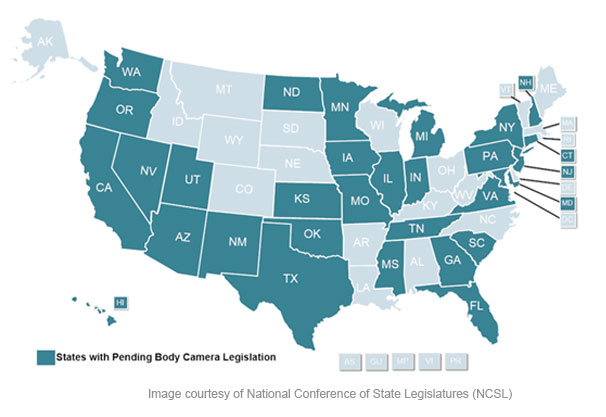

Per the National Conference of State Legislatures (http://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/law-enforcement.aspx), an increasing number of states—30 as of Feb. 20—are considering legislation that address body-worn cameras for police officers.

Proponents of body-worn cameras believe that video and audio recordings of law enforcement’s interactions with the public will provide the best evidence of, and defense to, accusations of police misconduct. They also believe that being on camera reduces some tension between police officers and the public. For example, a field experiment conducted on body-worn cameras with the Rialto, CA, Police Department found that incidents where police used force and community member complaints against police officers were reduced 50 and 90 percent respectively compared to the previous year.

Several municipalities—including Chicago (IL), the District of Columbia, Los Angeles (CA), New York (NY) and Seattle (WA)—have recently implemented body-worn camera programs and their experiences will inform body-worn camera policy moving forward.

While many are enthusiastic about the potential benefits of body-worn cameras, there are practical and constitutional hurdles to their implementation including funding, data storage and retention, open records laws, recording in areas protected by the Fourth Amendment and appropriate regulations for police use. Many of these and other issues are addressed in state legislation.

So far there have been few enactments addressing body-worn cameras by police officers, and all became law in 2014. Pennsylvania (30 Pa.C.S.A. § 901, PA ST 34 Pa.C.S.A. § 901) enacted legislation allowing waterway and game conservation officers to wear body-worn cameras and Vermont (VT ST T. 20 § 2367) enacted a law that, in part, requested a study of their use in conjunction with Tasers. Oklahoma enacted a law classifying video and audio files from body-worn cameras, if kept, as records under their Open Records Law. Oklahoma’s (51 Okl.St.Ann. § 24A.8) law also specified situations where video could be redacted prior to being released including portions that depict the death of a person or a dead body, nudity or the identity of individuals younger than 16 years of age.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) has dedicated $2 million to fund two or three body-worn camera (BWC) projects as part of the Smart Policing Initiative in fiscal year 2015. As part of President Obama's Community Policing Initiative, $20 million is available to support BWC purchases and programs in fiscal year 2015. The President has proposed an additional $30 million in the fiscal year 2016 budget. Finally, the BJA Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) is a valuable resource for communities to use to procure this equipment.

For more information, see:

- FY2015 BWC Pilot Implementation Program solicitation: https://www.bja.gov/Funding/15BWCsol.pdf

- 2015 JAG solicitation: https://www.bja.gov/Funding/15JAGStateSol.pdf

There are a handful of useful resources on body-worn cameras (BWC). The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) and the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) Office published a report in 2014 that examines key issues and offers policy recommendations. The report is based on survey responses from 254 agencies, interviews with 40 law enforcement executives who have implemented BWCs, and outcomes from a one-day conference held on September 11, 2013, that included more than 200 law enforcement executives, scholars, and experts. In April 2014, the Office of Justice Programs Diagnostic Center published a report that describes the core issues surrounding the technology and examines the state of research on those issues (White, 2014). In March 2014, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) published a market survey that compared BWC vendors across a range of categories. There is also a growing number of published evaluations that examine the implementation, impact, and consequences of body-worn cameras. This web site and toolkit is intended to be a clearinghouse of the latest available research, reports, and knowledge on the technology.

For additional information, see:

- National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center (NLECTC) for the National Institute of Justice, Primer on Body-Worn Cameras for Law Enforcement: https://nccpsafety.org/assets/files/library/Primer_on_Body-Worn_Cameras.pdf

- System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders (SAVER) for the Science and Technology Directorate, Body-Worn Video Cameras for Law Enforcement Assessment Report: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Body-Worn-Cams-AR_0415-508_0.pdf

- National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology (NLECTC) for the National Institute of Justice, Body-Worn Cameras for Criminal Justice: Market Survey: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/nlectc/245747.pdf

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

- Police and Crime Standards Directorate, Guidance for the Police Use of Body-Worn Video Devices: http://library.college.police.uk/docs/college-of-policing/Body-worn-video-guidance-2014.pdf

- Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Canada’s Guidance for the Use of Body-Worn Cameras by Law Enforcement Authorities: https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/surveillance/police-and-public-safety/gd_bwc_201502/

For additional evaluations from around the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, see:

- Phoenix, Arizona: http://cvpcs.asu.edu/sites/default/files/content/projects/PPD_SPI_Final_Report%204_28_15.pdf

- Mesa, Arizona: http://issuu.com/leerankin6/docs/final_axon_flex_evaluation_12-3-13-

- Isle of Wight, U.K.: https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/evaluation-of-the-introduction-of-personal-issue-body-worn-video-cameras-operation-hyperion-on-the-isle-of-wight(aa564df2-ffda-4b72-b0b6-7f9cb823aa77).html

- Paisley & Aberdeen, U.K.: http://www.bwvsg.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BWV-Scottish-Report.pdf

- Plymouth, U.K.: http://library.college.police.uk/docs/homeoffice/guidance-body-worn-devices.pdf

- Edmonton, Canada: http://www.cacole.ca/confere-reunion/pastCon/presentations/2014/maryS.pdf

- Los Angeles (CA) Police Department and Las Vegas (NV) Metro Police Department: http://nij.gov/topics/law-enforcement/technology/pages/body-worn-cameras.aspx#ongoing

Or view BWC Toolkit Research Resources with the category of Implementation Experiences

Public and media requests for body-worn camera (BWC) video are governed by local, tribal and state laws. As a result, law enforcement agencies should work closely with their legal counsel on this issue. States vary tremendously in the scope of their laws governing public access to government information, including BWC video, which is generally viewed as a public record. The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) cautions agencies to balance the legitimate interest of openness with the need to protect privacy rights. For example, releasing a video that shows the inside of a person's home will likely raise privacy concerns. Also, most local, tribal and state laws have a provision that allows an agency to decline a public records request if the video is part of an ongoing investigation. PERF also cautions agencies to use their exceptions to releasing video "judiciously to avoid any suspicion by community members that police are withholding video footage to hide officer misconduct or mistakes." (PERF, 2014: 18) Departments should also provide clear reasons for why they decline to release a video.

Department policy should also specifically prohibit officers from accessing recorded data for personal use, and from uploading data to public web sites. Departments should clearly articulate the punishments for such violations (PERF, 2014).

Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel participants further emphasized the value of having open forums to discuss BWC programs. Lieutenant Daniel Zehnder, Las Vegas (NV) Metropolitan Police Department, explained that they "hosted an extensive media day–set up scenarios and spent hours training local media on how the cameras work. We found this extremely important to build rudimentary knowledge." Matthew Scheider, Assistant Director for Research and Development at the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, suggested, "the key is for officers and policymakers to engage with the public before implementation; this engagement at the community level is critical. I encourage this group to think about the future of BWC–what does the future hold and what are the pitfalls it holds? One potential future and pitfall is facial recognition with BWC, including those in the background. The notion of FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) and access of records is important, and concerns over storage will get easier but community members will want access."

For more information, see:

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

Law enforcement agencies should consult with their local prosecutors and legal counsel as they design their data storage policies. Laws governing how long video must be stored may vary across cities, tribal governments, and states. Video that depicts an arrest or critical incident may have to be stored for an extended period of time. Departments have varied policies on how long they keep video that depicts an encounter where no formal action is taken. Some departments will store such video as long as a community member can file a complaint. For example, if members of the public can file a complaint for up to six months after an encounter with a law enforcement officer, it may be necessary to keep all video for six months so the video can be accessed to assist with the complaint investigation. State law may dictate the length of time for storage of more formal law enforcement encounters with members of the public. These are important issues that law enforcement agencies should discuss with their prosecuting authority before procuring storage systems or enacting any policies regarding storage.

Some departments classify body-worn camera video as either "evidentiary" or "non-evidentiary." Evidentiary video includes footage that can be used for investigative purposes, and many departments have created sub-classification systems of types of videos (homicide, use-of-force, arrest, mental health commitment, etc.). The length of time a video is retained is then typically determined by how the video is classified (evidentiary or non-evidentiary) and, if evidentiary, the type of encounter.

Many of those surveyed by the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) retain non-evidentiary video for 60-90 days. Regardless, retention times should be specifically stated in department policy, as should the process for data deletion. As an indicator of transparency, many departments publicly post their retention policies on their web site.

The PERF report (PERF, 2014) also identifies a number of data storage issues that should be covered by policy and put in place:

- The policy should clearly prohibit data tampering, editing, or copying.

- There should be technological protections against tampering.

- The department should have an auditing system in place that documents who accesses each video, when the access occurs, and why.

- The policy should identify who has authority to access video.

- Departments should develop a reliable back-up system for video.

- Law enforcement should provide guidance on when officers should download video (e.g., at the end of the shift).

- The policy should be explicit about the use of third-party vendors.

Each department must fully examine its state, local, and tribal laws to determine when it is lawful to record events. Most communities, however, fall into one of two groups.

The first group is composed of those communities that require one-party consent. In these communities it is lawful to record communication when consent is obtained from one person (e.g., officer, suspect, or victim). Within these laws, there might already be exceptions that would cover body-worn cameras (BWC). Nonetheless, in these communities, it is up to law enforcement to determine whether they inform the individual of the recording. The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) recommends that officers inform members of the public that they are being recorded "unless doing so would be unsafe, impractical, or impossible," (PERF, 2014: 40). PERF emphasizes that this does not mean that they are required to have consent to record, only that they inform the person that they are recording. The rationale for this is straightforward. If BWCs do produce benefits in terms of change in behavior (civilizing effect), those benefits can only be realized if the community member is aware of the recording.

The second group are those communities that require two-party consent. This means that it is not legal to record the interaction unless both parties consent to it being recorded. As stated above, there might also be exceptions within these laws that may cover BWC recordings. Two-party consent laws can present special problems to law enforcement agencies that are interested in implementing a BWC program because the law enforcement officers have to announce that they would like to record the interaction and obtain approval from the member of the public. As a consequence, some states such as Pennsylvania have successfully modified existing statutes to allow the law enforcement to use BWCs without two-part consent (Mateescu, Rosenblat and Boyd, 2015).

For more information, see:

- Data and Society Police Body-Worn Cameras (Mateescu, Rosenblat and Boyd, 2015): http://www.datasociety.net/pubs/dcr/PoliceBodyWornCameras.pdf

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

At a minimum, a law enforcement agency should collaborate with the prosecutor's office (city, county, state, federal, and/or tribal), the public defender and defense bar, the courts, and relevant leaders in local/tribal government (mayor, city council, city attorney, etc.).

The law enforcement agency should also engage civil rights/advocacy groups, community leaders, and residents. A number of agencies have also engaged local media in the process to educate the public, advertise the decision to adopt the technology (i.e., to demonstrate transparency), and provide a mechanism to gather feedback.

In March 2015, there were nearly 30 states considering legislation governing officer body-worn cameras (BWC), many of which mandate cameras for all law enforcement officials in the entire state. Law enforcement leaders should also engage state representatives to ensure that legislatures fully understand the issues surrounding this technology, and that they engage in thoughtful deliberations regarding BWCs. By engaging external stakeholders, the law enforcement agency can ensure that expectations about the impact of the technology are reasonable and their outcomes obtainable.

Questions from community members are likely to focus on several key issues. The first involves aspects of body-worn camera (BWC) policy. For example, community members will likely ask questions such as: when will officers turn the camera on? Do they have to tell me before they turn it on? Can I ask the officer to turn the camera off? Am I allowed to request a copy of the video?

Community members are also likely to ask privacy-related questions, such as: Are officers allowed to film in my house or apartment? What happens if the officer records my children? Who is allowed to watch the video? Is this video going to end up on the internet or YouTube? Will my neighbor be able to see this video?

Community members may also want to know about the goals of the BWC program. They may ask: Why are police officers wearing BWCs? What does the agency hope to accomplish with BWCs? Will all officers be wearing cameras? BWCs will have a significant impact on community members, and community buy-in is critical to the success of a BWC program. As a result, law enforcement agencies should be prepared to provide detailed responses to these and other questions.

Public and media requests for body-worn camera (BWC) video are governed by local, tribal and state laws. As a result, law enforcement agencies should work closely with their legal counsel on this issue. States vary tremendously in the scope of their laws governing public access to government information, including BWC video, which is generally viewed as a public record. The Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) cautions agencies to balance the legitimate interest of openness with the need to protect privacy rights. For example, releasing a video that shows the inside of a person's home will likely raise privacy concerns. Also, most local, tribal and state laws have a provision that allows an agency to decline a public records request if the video is part of an ongoing investigation. PERF also cautions agencies to use their exceptions to releasing video "judiciously to avoid any suspicion by community members that police are withholding video footage to hide officer misconduct or mistakes." (PERF, 2014: 18) Departments should also provide clear reasons for why they decline to release a video.

Department policy should also specifically prohibit officers from accessing recorded data for personal use, and from uploading data to public web sites. Departments should clearly articulate the punishments for such violations (PERF, 2014).

Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel participants further emphasized the value of having open forums to discuss BWC programs. Lieutenant Daniel Zehnder, Las Vegas (NV) Metropolitan Police Department, explained that they "hosted an extensive media day–set up scenarios and spent hours training local media on how the cameras work. We found this extremely important to build rudimentary knowledge." Matthew Scheider, Assistant Director for Research and Development at the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, suggested, "the key is for officers and policymakers to engage with the public before implementation; this engagement at the community level is critical. I encourage this group to think about the future of BWC–what does the future hold and what are the pitfalls it holds? One potential future and pitfall is facial recognition with BWC, including those in the background. The notion of FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) and access of records is important, and concerns over storage will get easier but community members will want access."

For more information, see:

- Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) for the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned: http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

There are limitations to body-worn cameras (BWC), and agencies should educate the public, advocacy groups, and other stakeholders regarding those limitations. BWCs may not capture every aspect of an encounter based on camera angle, focus, or lighting. For example, the camera view may be obscured when an officer moves his or her body. Footage may also not capture the entirety of an encounter. There may be different interpretations of what transpires on a video among those who view it.

There is also a relevant body of research on memory science: how officers perceive events during a high-stress critical incidents, and how they are able to accurately recall what transpired after the fact. Dr. Bill Lewinski, Executive Director of the Force Science Institute, testified before the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing regarding memory science and how such issues provide an important context for understanding the impact of BWCs. Dr. Lewinski identified 10 important limitations with BWCs that should shape our review and understanding of law enforcement behavior during critical encounters:

- A camera does not follow officers' eyes or see as they see.

- Some important danger cues cannot be recorded.

- Camera speed differs from the speed of life.

- A camera may not see as well as a human does in low light.

- An officer's body may block the view.

- A camera only records in 2-D.

- The absence of sophisticated time-stamping may prove critical.

- One camera may not be enough.

- A camera encourages second-guessing.

- A camera can never replace a thorough investigation.

Participants at the February 2015 Bureau of Justice Assistance BWC Expert Panel also stressed the importance of communicating the limits of the technology. Michael Kurtenbach of the Phoenix (AZ) Police Department said, "Sit down with the community and have discussions about limitations for a constructive dialogue." Inspector Steve Goodier from the Hampshire Constabulary in the United Kingdom added, "There is a gap in the limitations of the human and camera, and it is important to make that distinction."