When a young person decides to carry a loaded gun, the outcome can be a felony charge, a prison sentence, and a spiral that ends in lost opportunities—and lost lives. With the right intervention program that focuses on behavioral training and job placement, young people can make life-affirming choices that prevent violence as a solution to conflict.

The Bronx-Osborne Gun Avoidance and Prevention Project (BOGAP) provides a violence intervention and prevention program for people ages 16 to 30 with a first-time felony charge of loaded-gun possession. After successfully completing the one-year program, the felony charge is reduced to a misdemeanor.

BOGAP is the result of a four-year collaboration between the Osborne Association, a nonprofit organization working to address the impacts of the criminal justice system in New York, and the Bronx District Attorney’s (DA) Office, which refers eligible participants to the program. The program received funding through the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) as part of the FY 2022 Office of Justice Programs Community Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative, which is allowing it to double its size and continue its mission to reduce and prevent gun violence by transforming attitudes and building job skills.

Addressing an Emergency

Approximately 27 percent of shootings in New York City are concentrated in just 6 of the city’s 77 police precincts—4 of those in the Bronx. The Bronx consistently has the highest gun possession and gun violence rates among young adults out of all the New York City boroughs, says Maurice De Frietas, BOGAP Program Manager.

But it was an escalation in first-time gun possession arrests among youth ages 16-30 that led to BOGAP addressing the underlying causes of gun possession. The immediate goal is for participants to put down their guns and avoid the long-term negative impacts of incarceration. Long term, the goal is for participants to live in safety, have a lasting transformation of attitudes and beliefs, attain financial self-sufficiency through employment, and become positive contributors to the community.

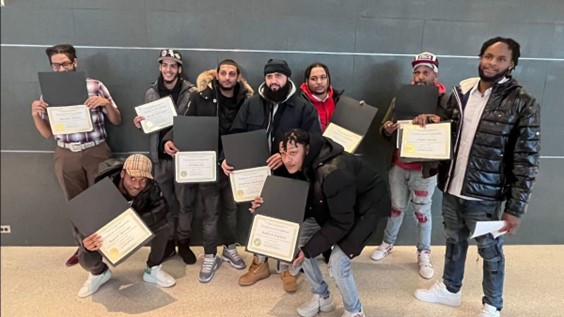

The program has already produced graduates who are successfully achieving these goals. In January 2023, BOGAP’s first group of nine graduates completed the program's 20-hours-per-week, one-year training course and had their charges reduced in court. Another group graduated in February.

“We’ve had an 80 percent completion rate, and because of the funding we’ve received from BJA, we have been able to expand to a total of 34 participants this year and have goal of increasing to 75 participants annually.” — Maurice De Frietas

Keeping participants out of prison also provides cost savings to taxpayers, another benefit of a high program completion rate.

Mindset Transformation

Crucial to the program’s violence prevention focus is changing how participants think about themselves and how they react to those around them, a first step when they enter the program. Participants engage in cognitive behavioral intervention (CBI), which includes interactive journaling and group classes to change attitudes, beliefs, and behavior. They also take part in dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) to address the trauma that underlies emotional volatility and impulsive behavior. Through the Alternative to Violence Program (AVP) component, participants build non-violent conflict resolution skills.

“We talk about over 6,000 weapons seized by the police in NYC, and what we have to do is look at the individuals who actually had those weapons, the reason why they had those weapons, and look at the way they think,” says EL-Sun White, Senior Case Manager and Court Advocate with BOGAP. “We’re not reducing the seriousness of having a weapon, but we want to get them to change their thinking” and choose nonviolent resolution, he adds.

Gregory Brooks, a BOGAP Credible Messenger who mentors groups of young men daily, gives an example of how training in peaceful intervention has replaced violence as a response to real-life situations. One day, several BOGAP participants were having lunch outside, “and they saw someone being jumped by three or four other guys. They didn’t know these people. They immediately ran over and deescalated the situation,” he says.

“Our participants have not only embraced what we do, but they take it outside in the streets. So what we're seeing when it comes to reducing and preventing violence is that they're applying what we do in the classroom to what they see outside, not only for their own lives but for the lives of other people in the community as well.” — Gregory Brooks

See the sidebar A Peaceful Interruption for another example of BOGAP participants actively resolving a violent situation in the community.

Choices and Concepts

When program participants see that they have options for problem-solving other than using weapons, they are actively preventing violence. The program gives young people choices, says Bruce Simpson, BOGAP Program Coordinator. “When you're provided with choices, you can figure out the best response in difficult situations.”

For example, if a person bumps you on the train, says Simpson, you understand that there's a choice not to personalize the bump, and you also understand that you're in a crowded train and it just might happen. So your response becomes different.

“In training, we put this concept into an acronym—Q.T.I.P., which means ‘Quit Taking It Personal,’” says White. Another concept they use is the formula E + R = O. “E means event, R means response, and O means outcome,” White explains. “You cannot control the events that come into your life, but you can control how you respond to them. And if you can control how you respond to them, then you control the outcome.”

This method of putting bits of guidance and wisdom into easy-to-remember catchphrases helps participants quickly internalize new response options, according to Susan Gottesfeld, Chief Program Officer and Executive Vice President at Osborne. “The way that this team makes those concepts available gives a lot of opportunity for reflection and for practice. This changes participants’ thinking at the root level, and it’s pretty incredible,” she adds.

The Right Mentors

Having mentors who are from the same neighborhoods work with participants is critical to the program’s success. Known as “credible messengers,” these staff, some of whom have been active in gangs and experienced long incarcerations and parole, interact with participants as leaders who have “been there” and can show them how to turn their lives around. Being a credible messenger “means that you can identify with a young person and walk beside them and show them how to do something different,” says Simpson.

“Participants know that we're not judging them or taking information that we're receiving from them and using it against them, and that's one of the things that makes it possible for us to achieve such a high a success rate, because the participants are not hiding themselves from us,” says Brooks. “They're being transparent, which gives us the opportunity to start to unpack some of the damage that's going on in their lives and help them address those issues.”

Brooks recounts a classroom incident that demonstrates both the skills of program mentors and the respect and trust participants have for them. “A group of participants were together, and one came into the room and whispered in my ear, ‘Can I speak to you for a second?’ So I took him outside to have a one-on-one, and he told me one of his enemies was there, and that he had a real beef with this person that included gunshots and people from both sides being killed. He thought that it was a very dangerous situation being in the same room with the guy.”

The fact that, rather than walking into the room and attacking his enemy, the young man came over and whispered in Brooks’ ear shows respect for him as a trusted leader and someone who could help the youth make a change in his life and possibly do something about this dangerous situation, says De Frietas.

Brooks arranged to bring the two young men together, who formerly had been shooting at each other in the streets, and helped them understand that they had common ground—including that they were both in the program to have felonies reduced. The young men started working together to help each other succeed. “They were able to put the animosity that they had to the side and resolve it. Some of their peers saw that they had reconciled and shared that on the outside. In doing so, they prevented additional violent issues that could have happened later on,” says Brooks.

Job Readiness

After BOGAP participants complete behavioral training, they advance to job readiness training, paid internships, transitional employment, and permanent job placements. “We focus on individualized service plans that address their employment goals and push them toward independent living and long-term employment,” says Brooks.

With the help of BJA funding, BOGAP can offer the further education participants need, says De Frietas. “For instance, we’ve had participants earn CDLs [commercial driver’s licenses] and vendors licenses to sell street food. So when we see that the need is there, we provide that support for them.”

Many program participants have never had a job, adds White. “We are helping them adjust to a work culture where they are earning a paycheck and learning to be responsible. And that's something different for them, knowing that whatever behavior they had prior to coming to the program is limited. That’s no longer their heritage, and they don’t need that anymore.”

Accountability and Successful Completion

All program activities emphasize personal accountability and support cognitive connections between thoughts, behaviors, and outcomes. Participants must complete the 20-hours-per-week attendance requirement, show up on time, complete all curricula, and stay actively engaged in the process. Osborne provides monthly reports in writing to the DA, the judge, and defense counsel.

When participants have met all the program requirements, they go back to court, where a potential seven-year felony sentence is reduced to a misdemeanor, says De Frietas. However, successful completion of the program is a much broader concept. Participants are successful when they are able to use the skills they learned without going to jail, carrying a firearm, or committing violence in their community.

Graduation is just a ceremony, says Brooks. The real measure of success is when graduates “make the decision to start changing their behavior, to stop picking up the gun, to use conflict resolution before they take action or do something that might jeopardize themselves or somebody else.”

Building a Legacy

For jurisdictions interested in adopting BOGAP principles and practices, Brooks advises ensuring there is appropriate training to lead and manage participants and demonstrate complete commitment to helping those with a history of gun violence turn from that life. “You must have the right intent, which is to make these young people successful,” says Brooks. “You must show that you are credible.”

“We can't look at these individuals as rapacious, uncivilized predator individuals,” says White. “We have a responsibility to look at them as good young men who made bad decisions, and we’re going to show them that they could liberate themselves by doing what they need to do in this program and allowing us to help you.”

"This is a labor of love,” says De Frietas. “Everybody here would do this for free.”