What Is Risk Assessment

Local, state and federal criminal justice agencies have increasingly adopted data-driven decision making to supervise, manage, and treat justice-involved populations. As a cornerstone of this movement, risk assessment is used across various stages of the legal process to assess an individual’s risk of reoffending (or noncompliance with justice requirements) and identify areas for intervention. For example, risk assessments are used pretrial to inform decisions about release pending adjudication or jail detention. Risk assessments are also used by correctional departments to determine the appropriate programming for incarcerated individuals. Probation and parole departments use risk assessment to set the level of supervision, including home confinement and electronic monitoring. Further, risk assessments are used by case managers and treatment providers to identify needs and link individuals to appropriate services as part of reentry and supervision plans. Once risk and needs are properly and timely identified, criminal justice agencies can then be more effective in ensuring public safety through the appropriate management and rehabilitative programming of justice-involved individuals.

Although risk assessments take various forms and require differing sets of information, most are actuarial rather than clinical, meaning they systematically quantify an individual’s risk of reoffending. These quantified “risk scores” help practitioners make operational decisions regarding the classification, management, and treatment of justice-involved populations. Generally, individuals with higher risk scores are assigned more restrictive conditions or referred to more intensive services (interventions), while those with lower risk scores are supervised under less restrictive conditions or receive minimal intervention. Similarly, for risk assessments that include criminogenic needs (i.e., dynamic factors linked directly to criminal behavior), individuals with higher scores in needs domains receive more intensive case management and treatment planning and services than those with lower scores.

Learn more about Risk Assessment Basics

Importance of Using Risk Assessment

Risk assessments can help practitioners systematically synthesize information about justice populations and more efficiently distribute limited justice resources. Criminal justice systems lack the resources to provide intense supervision and treatment to everyone who comes into contact with the justice system and must instead decide on whom to target available resources. Further, research has shown that individuals at low risk of reoffending can be successfully managed with minimum or no supervision and may even be harmed by more intensive monitoring and treatment. It thus makes sense to assess individuals’ risk and needs systematically and focus limited resources on those with the greatest risks and needs.

Ultimately, the importance of using actuarial risk assessment tools across criminal justice settings and stages is defined by improved consistency, efficiency, and effectiveness.

Consistency

- Systematic risk assessment improves the consistency of data informing criminal justice decisions and the processes by which such decisions are made. In this way, decisions guided by risk assessments can be viewed as more defensible and credible than more subjective and less transparent decision-making processes.

Efficiency

- Data-driven risk assessment can help practitioners make more efficient use of limited justice resources. Actuarial risk assessment consistently emerges as superior to professional judgment in predicting reoffending risk, yielding more efficient decision-making heuristics.

Effectiveness

- Detailed risk assessments using empirically valid tools can help practitioners more effectively improve criminal justice outcomes (e.g., reduce reoffending, improve compliance). Risk assessment scores also provide a richer picture of individual variation in program effectiveness, helping practitioners determine what works for whom and why.

Illustration

Figure 1 demonstrates how risk scores are calculated in risk assessment. For the sake of illustration, this hypothetical example only covers five domains of predictors, including demographics, criminal history, education/employment, family/social support, and antisocial cognition, and only one indicator for each domain. Values on each indicator have been assigned scores ranging from 0 to 2; the higher the score, the more likely one is to reoffend (e.g., because younger persons are more likely to reoffend than older persons, values on the “age at sentencing” indicator decrease as age increases).

1

DEMOGRAPHICS

Age at sentencing

Select One

2

CRIMINAL HISTORY

Prior juvenile commitment?

Select One

3

EDUCATION / EMPLOYMENT

Currently employed

Select One

4

FAMILY / SOCIAL SUPPORT

Support from family / friends

Select One

TOTAL SCORE

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

0 - 2 Low Risk

3 - 5 Moderate Risk

6 - 8 High Risk

Conducting Risk Assessment (“Four Cs”)

There are four steps (“four Cs”) involved in risk assessment and management:

- COLLECTING INFORMATION;

- CALCULATING SCORES;

- CLASSIFYING INDIVIDUALS; AND

- CUSTOMIZING JUSTICE SYSTEM RESPONSE.

Understanding Risk Assessment

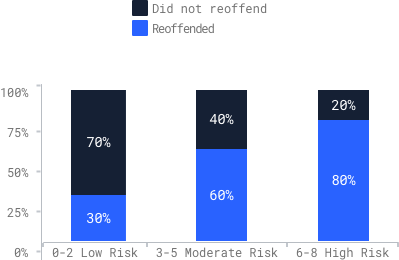

Understanding how risk assessment can aid criminal justice decision-making necessitates two important distinctions. First, risk assessments provide a probabilistic but not definitive prediction of an individual’s likelihood of reoffending. Risk assessment can help practitioners understand how likely an individual is to reoffend, but it cannot predict a person’s behavior with certainty. For example, the individual assessed in figure 2 with a risk score of 6 would be in the high risk group in example 3, for whom the average reoffending rate was 80% over a specified time period (e.g., 5 years). This risk assessment provides a probabilistic statement: on average, 80% of individuals with a similar level of risk characteristics will reoffend. Conversely, it can be interpreted as individuals with that risk designation would have an 80% chance of reoffending.

In practice, the accuracy and validity of assessment tools can vary greatly, so it is important to understand the empirical strength of a tool for the population on which it is to be used. Helping practitioners identify the most appropriate risk and assessment tool for their population is a key goal of the Public Safety Risk Assessment Clearinghouse.

A second distinction for practitioners to understand about risk assessment is that between static and dynamic risk indicators. Static indicators imply the inability to change (e.g., gender, race), while dynamic factors may be changeable with proper intervention. Practitioners looking to lower an individual’s risk of reoffending should focus on identifying risk indicators that are potentially changeable, such as delinquent peer association. Case management and treatment planning efforts should focus on these changeable, dynamic risk factors to the extent that resources permit. Given that risk indicators can change over time, practitioners must also realize the importance of repeating risk assessments as an individual’s life circumstances change